Vapor, Jelly, and Concrete

Building something new is a deliberate process of moving from some level of uncertainty to a high enough level of certainty. Every idea in its infancy is surrounded by any number of unknowns. This is just the name of the game. That uncertainty drives a lot of people crazy.

Fortunately, there is any easy way to resolve this: focus on whatever has the highest level of certainty, make it your rock solid gospel truth, and build based on that assumption.

Unfortunately, that easy way is a path to pretty certain failure1. In truth, that’s rarely the first step anyone takes, but I’ve seen so many products land flat because the tolerance for uncertainty was exhausted, so the team scoped down and delivered something that was feasible but not all that valuable2.

Tolerance for uncertainty is a muscle that you can build. Let me just say: this is a well-exercised muscle in my life, like to the point now that I think it might be one of my superpowers. Like to the point that it’s one of the things people pay us to do at Routine Chaos3 - work through the uncertainty to find a way to something real.

Over the past few months, in particular, I’ve worked with 2 different teams to bring 2 major projects from vague ideas to real, tangible, actual things.

And that’s got me thinking: the way you build muscle is through exercise

(and like any muscle, there is a healthy upper limit on how far you want to develop it, but let’s save that for another day), and what’s the exercise that helps build a tolerance for uncertainty and an ability to navigate through the uncertainty?

And I’ve got one for you. This is something that I do on almost every project where I’m working with a team somewhere near the beginning when we’ve probably done a little bit of early discovery and are starting to make sense of it all.

Let’s talk about Vapor, Jelly, and Concrete.

But first, a little story

The first couple days of the first Futureshock pilot were kind of a mess. We had spent a bunch of our time developing these games and hadn’t fully play-tested the final versions we were using, and they just weren’t landing. Lots of participants had essentially 0 interest in the games, and we had this hour long block every day for games and no real back up plan.

And we weren’t freaking out about it, because we knew that the games weren’t actually the most critical piece of the Futureshock experience. The interest-driven projects were, and while there were still a bunch of kinks to work out, we had tested our biggest risks and challenges related to interest-driven projects, and we were very confident in that piece. That confidence was actually what gave us the freedom to take this uncertain bet on the games, because we knew it would be epic if it worked but wouldn’t tank the whole thing if it didn’t.

It didn’t work, but because we weren’t rattled by that we were also able to get a ton of useful insight from that failure and make some tweaks.

This is how navigating the uncertainty often looks.

Vapor, Jelly, and Concrete…

What it is

It’s an exercise to first, filter through a mess of different insights, and then to identify where to focus in order to take the next step forward. This is most helpful when you have a whole lot of thoughts, but you’re not sure what to do with them.

Why do it

The simple version is: because you need to know where to focus your effort. Resources are always limited in some way, whether it’s people, cash, or time. You want to know which bets you should make when you can’t make all of them right away.

How to do it

It’s basically 3 steps. You can do it on a whiteboard (analog or digital), and it’s even better as a team sport where you can get more than one perspective. Here’s my basic template for the exercise in Google Slides (feel free to make a copy and follow along).

Step 1: Dump Insights

Get all of the big stuff in your head out - what are your current assumptions, hypotheses, insights? What risks have you identified? What ideas do you have about opportunities. Just drop each one on a post it note. Don’t worry about structuring anything at this point, just get as much out as you can.

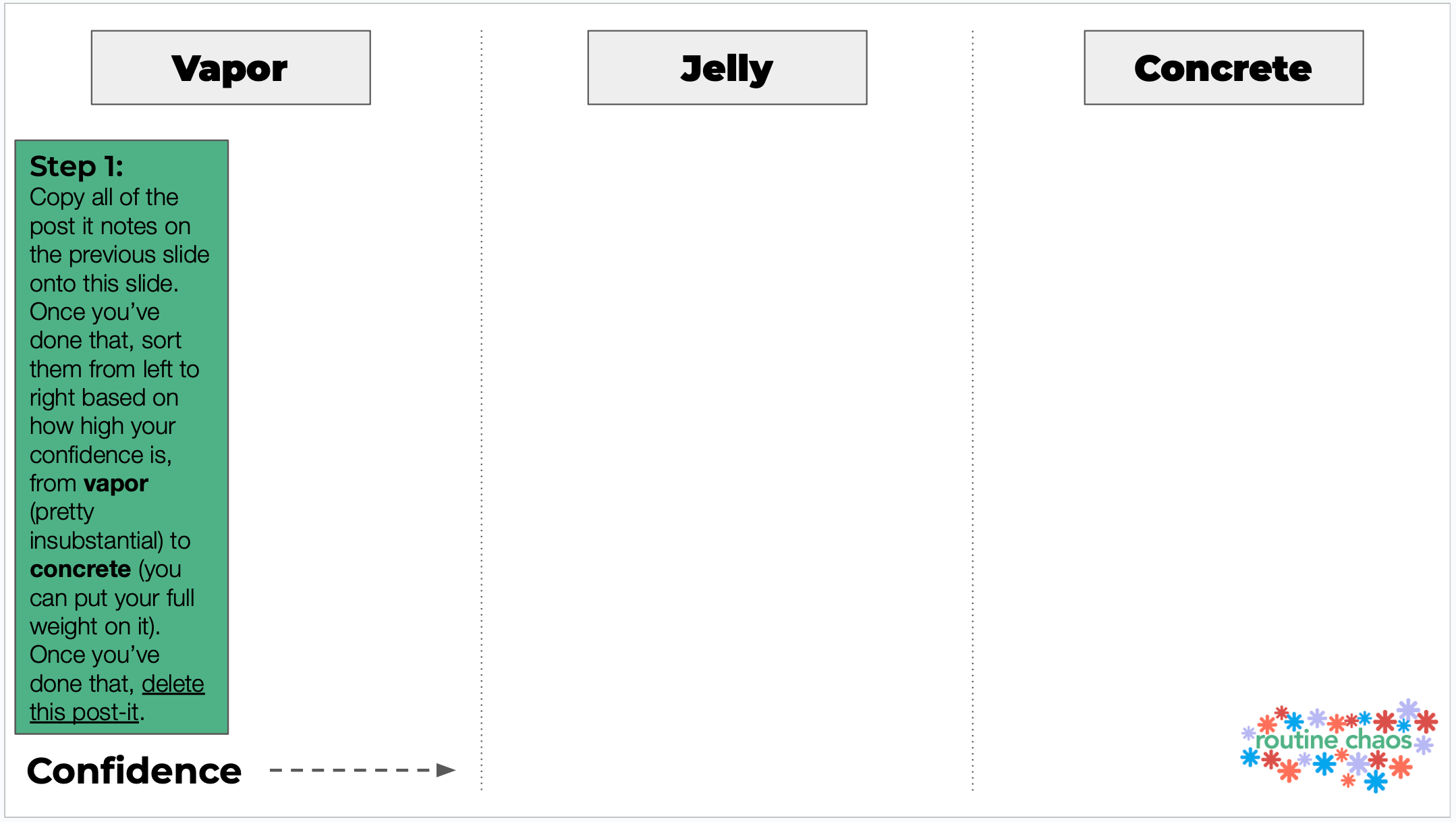

Step 2: Assess Confidence

Now you’re going to start making sense of them. For everything you’ve just dumped, you’ve got a level of confidence in it. Start by putting each in to 1 of 3 categories:

- Vapor - you don’t have much confidence in this yet. It’s an idea, maybe an intuition that you can’t quite justify. For something vaporous, a lack of evidence isn’t a problem…but you probably don’t want to make a huge bet on vapor.

- Jelly - this is more substantial than vapor. You might have some data or more substantial context here. You have a pretty good sense that there’s something to it, but you’re not sure that you’ve defined it quite right yet. You’d make a bet on it, but bigger bets would feel like pretty significant gut checks.

- Concrete - it’s solid. You know that you know that you know this. You can trust that this will hold up no matter how much weight you put into it.

Remember: these categories together form a spectrum, and there’s a spectrum within them. Some things are rock solid concrete, and some maybe have a few cracks in them. By the end of this, ideally you’ll have built the spectrum with the most vaporous piece on the left on the most solid piece on the right.

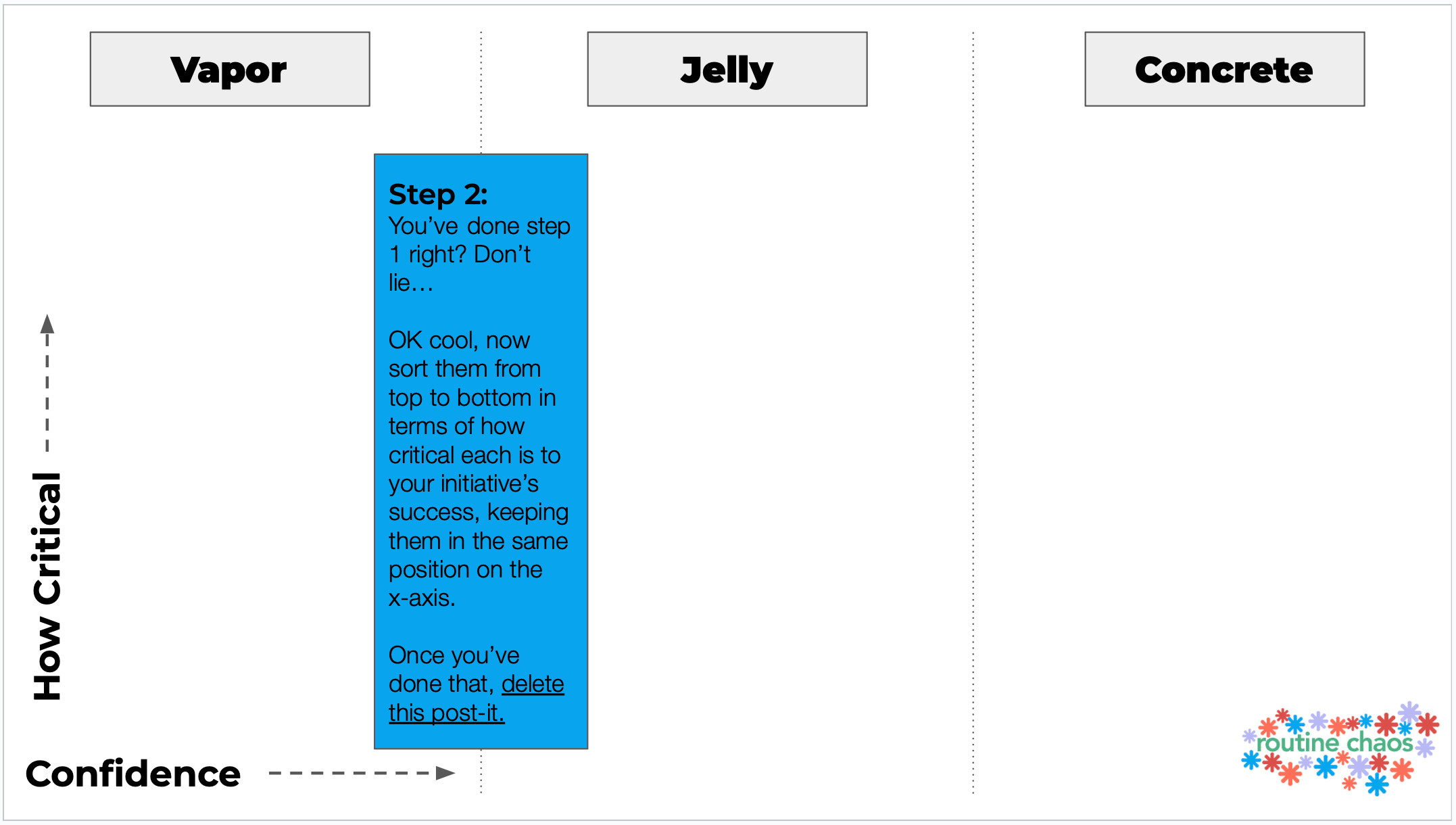

Step 3: Rank by Criticality

Not all of these insights are created equal. Some of them are things that you absolutely have to get right, some of them are just nice to have. This is what you’re going to figure out now.

You’ve got your confidence on the x-axis…don’t change that, but now move each post-it along the y-axis based on how critical it is to the success of your initiative based on your current understanding of things. The higher it goes, the more critical it is that you get it right.

(Going back to why new initiatives often fall flat when they’re build from a starting place of high certainty - they’re often high confidence but low criticality. You can execute on them - which feels good! - but they aren’t actually the core of what you need.)

If you’re wondering why we don’t start with criticality, it’s simple: when we start there we lie to ourselves. We put the things that we’re confident in high on criticality even when they’re not, and we undervalue the things we’re not confident in because of the uncertainty.

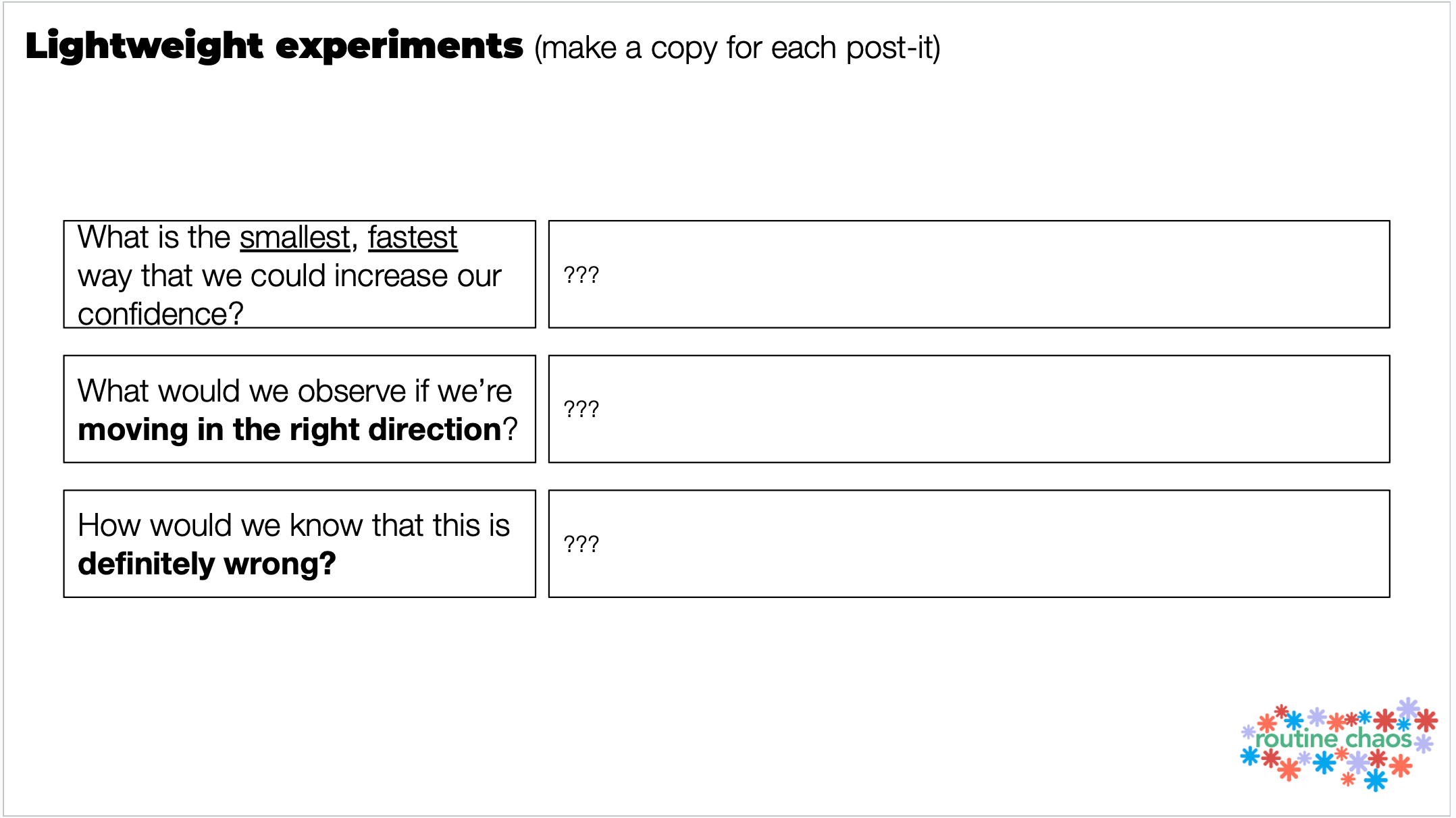

Step 4: Create an Experiment

At this point, you should be able to see what your most critical area to focus on is. You might even have a few.

Your temptation will be to figure out how you move them all the way to rock solid concrete right away. Therein lies the road to “pound your head against the wall” frustration.

The ultimate goal is concrete, yes, but the immediate goal is to move your confidence in your most critical area as quickly as possible. Trying to make a big jump will lead you toward something that’s going to take a lot of effort that may be completely in the wrong direction.

Getting to concrete is going to start with a quick, cheap, dirty experiment. If you’re in the vapor stage, something that you can design and test in a couple of hours is ideal. The biggest question you’re answering is, “are we moving in the right direction with this?” And you’ll know that because you’ll do something that gets you a bit of evidence that you are. (Please, though, for the love of all that’s holy, don’t do a survey. Do something that will give you a measurable or observable behavior. Please? Unless you’re very well-trained in how to design good surveys.)

Wrapping Up

You run the experiment and maybe your confidence increases, but maybe you realize you’re moving in the wrong direction. Either way, you’re into an iterative loop - you’re looking for the next experiment you can do to get confidence in something critical. It may be further testing of the same thing, but it may be time to look at the next big risk area.

The Vapor, Jelly, Concrete exercise gives you a living artifact. You’ll update it over time, moving things left and right in confidence, up and down in criticality (because, yes, you were probably wrong about some of it). You’ll add new things in, you’ll strike some things out.

You’ll find your way.

But, of course, if you’re in need of a seasoned guide, drop me a line.

Man, I feel sorry for anyone who only read the first two paragraphs and then bailed out to go and build something. ↩

And if you think you’ve found an incredibly feasible, incredibly high value solution that no one else has stumbled onto yet, proceed with caution; you’re probably wrong. ↩

Like to the point that it’s embedded in the name… ↩

Member discussion