The Traveling Circus

Chautauqua

A few months ago, I was reading up a bit on the Chautauqua circuit, this late 19th/early 20th century phenomenon where a group of lecturers would go on tour around the eastern US during the summer, and families would decamp to some rural area for a few days to listen to this group of lecturers under a bigtop circus tent. It was this whole multi-generational education approach that was quite popular among certain groups for a few decades.

My reaction was a bit mixed.

On the one hand, I remembered the seething jealousy I felt toward a group of friends from my early twenties who were in a band and one summer bought a very used biodiesel schoolbus, tore out the seats inside, added in some beds & storage, and took off on tour for the next few months. They'd drive around to the venues they were playing in, and then afterwards they'd convince the venue or some other nearby restaurant to let them empty out the grease trap so they could filter it and fuel the bus back up1. Like, what could be a better way to spend the summer than touring around with people you enjoy and stopping periodically to do some sort of popup event?2

On the other hand, lectures? Ugh. Yeah, it's basically like proto-TED...with longer talks. Not only is this not my cup of tea, it just seems so desperately far away from a compelling vision of what multi-generational learning could be.

What would it look like to have a traveling circuit of pop-up events that centered participation and co-creation, rather than observation? Maybe a touring version of Theater of the Mind? Even that doesn't quite scratch the itch. A touring version of Recurse? Possibly.

Futureshock

I've spent a long time down this rabbit hole over the past few months, and on Sunday I jump on a plane to spend most of my summer on tour with Futureshock, a pilot project I've been developing together with some friends at the Reinvention Lab.

Over the next couple months, we're going to do 2 week pop-ups of this mash up of game-based learning and self-directed projects in Tennessee, Idaho, and California. We've created 6 different tabletop games for small groups and a few generative-AI tools that go along with them.

Here's the biggest bet we're making with this: most people have a project in them that they're intrinsically motivated to work on...they just need the right support to define it and overcome enough of the initial challenges so that it becomes satisfying to work on.

And there's a deeper why behind it that maybe merits its own post, but I'll just share it briefly here: career pathways are dead. For people coming of age right now, one of the most important skills they need is the ability to work on projects that each draw on different sets of skills. They'll need to regularly cultivate new skills and use them in tandem with existing skills in novel ways. Many of those skills we can't even name today because they don't exist...though they will probably be built on the foundation of skills that do exist.

So...my hope is that Futureshock is a thing that helps participants identify some of their strengths, skills, and interests and find ways to combine them to work on something meaningful.

A digression

Launching something new is scary. It fills me with excited nerves and muscle-clenching anxiety like nothing else. Because no matter how much preparation you put into it, you never know exactly how it's going to play out. Sometimes rockets with tens and hundreds of millions of dollars of R&D spend behind them blow up on the pad. Sometimes a film that hundreds of people have spent months of their lives on falls flat.

To take you behind the curtain, back in early March we had a design critique for this project with a panel of outside advisors. This was very much in the spirit of Pixar's Brain Trust. At the time, Futureshock was something different called Summer Amp. We presented it to this group of people who we really respected and whose insight we really valued, and to succinctly summarize their response, they said, "Meh." It wasn't bad; they were able to draw out some aspects where it had potential, but they thought we were playing it safe and consequently building something that was just fine but nobody would particularly love.

Kind of not my favorite moment, but low key: kind of my favorite moment? You invite these people into a space like that for them to tell you the hard stuff. They did. They weren't wrong.

This is a thing that happens often in projects and never gets caught: you start with some ambitious aspiration, it turns out to be hard, you figure out a way that 70% of the way works, you downgrade your ambition, and you roll with it. Sometimes that's fine...but probably a lot less often than what we tolerate.

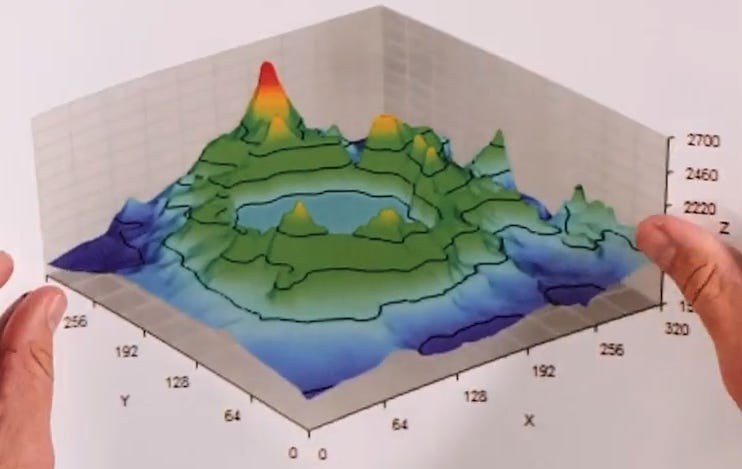

Mark Rober articulates this really well in his Creative Engineering class using this diagram:

The idea is that you're trying to get to that red peak. Your first ideas probably land somewhere in the green, and you need to keep pushing just a bit more to get into the red...but that's the part that's really hard. The obvious ideas and insights all got spent to get you to the green. You need to get creative to get to the red. That last final bit consumes a disproportionate amount of your time and energy.

But - and this is what you learn if you land it just one time - that's what makes it all worth it. And it's hard to not at least shoot for the red going forward.

Real Talk

I don't think Futureshock is going to be a dismal failure. After that design critique, our team immediately regrouped and decided to chase after the red. We've had a few moments of incredible insight since then. The process itself has been worth it.

And I still don't know that it will totally land. I am very hopeful. I think there's something special there. We have 3 pop ups this summer, so 3 opportunities to refine and iterate.

Wish us luck!

Oh wow, and thanks to the magic of the internet you can actually still find some remnants of the band. ↩

Yes, this is also one of my favorite things in Station Eleven. ↩

Member discussion