Reflections from inside the maze

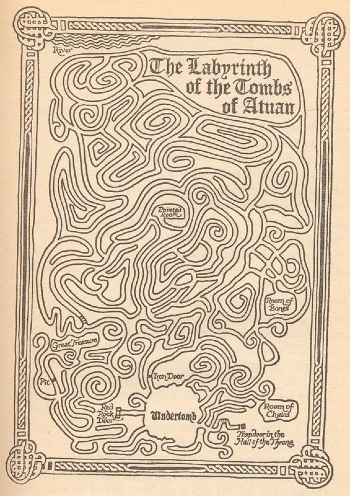

The core of Ursula K. LeGuin’s book the Tombs of Atuan takes place in the darkness, specifically in the depths of an underground maze that hold the inner sanctum of the temple for the gods of a dying religion. Light is forbidden, and only the highest of the high priestesses dares set foot inside it - and even then with the knowledge that if she isn’t attentive to every detail of her journey inward, then she will become lost within and die there because no one else can come to her rescue.(If you’re thinking this sounds like an excellent book, go back to the beginning of the paragraph: it was written by Ursula K. LeGuin, of course it’s excellent.)

I find this premise provocatively terrifying, simultaneously repulsive and compelling. It reminds me of how I felt standing on the observation deck of the Burj Khalifa as a person who is both afraid of heights and always seeking out the tallest buildings and going to the top of them. It’s a fear based on unimaginable possibility.

Wandering in the pure darkness. What fresh hell is this? But also, what if you actually find something there? Both things coexist in my brain at the same time.

And, of course, LeGuin mines the richness of the pitch black maze as extended metaphor of the Faustian bargain where an appearance of power & knowledge is actually a trap to enslavement.

A week after I finished reading Atuan, I found myself wandering through a maze - this one much less metaphorical, much less existential, much more joyful. This maze was at the core of an impeccably designed experience that immersed the wanderer in being both ephemeral and separated from time.

Because I’m allowed to nerd out here, let me just narrate a few of the ways that they accomplished this phenomenon:

- No phones & no cameras inside the maze. Consequently, very little documentation of what lies inside the maze (this also happens in Atuan, but more because of a resistance to writing & drawing within the dying religion). Anything you share about the maze comes after you’ve exited the maze and depends on your own memory, and memory can be such a finicky thing.

- No watches inside the maze either. Consequently, no way of keeping time. Once you’re in, you’ll only find out how long it’s been when you leave. The maze is discursive rather than linear, so it’s not as if you simply chart a single path through it.

- You may arrive in a group, as I did, but the staff takes you to enter the maze one at a time. Also, the maze has multiple points of entry, so while you may eventually find your friends, you enter and begin your exploration entirely as an individual.

There were several other elements that encouraged the maze wanderer to slow down, take note, really see what was happening. The sensory cueing was on point. BTW, if you want to go deep down the rabbit hole on designing emotionally evocative experiences, I beg you to hit up Olivia Vagelos’s Substack.

Needless to say, I loved the maze. I loved the occasional moments when it involved making my way through actual pitch blackness. I loved the uncanny moments of discovery. I loved finding multiple ways to come back to the same point. As I went through, I began to get a sense that I might actually be doing a lot of it backwards…at one point, as I was crawling up a long slide and hoping that nobody was coming down on the other end, I was quite sure I was doing it backwards. The terrain itself was novel, but navigating it felt entirely familiar.

It reminded me of something I said to my therapist the week before: sitting in the unknown, the uncertain, the ambiguous is kind of my superpower.

In the early stage exploration and prototyping work I do with clients, I’d argue it’s actually what they’re bringing me in for. We have to give it more formal names, like journey mapping, developing problem cases, building proofs of concept, etc…but the truth of the matter is:

I’ve seen too many examples of initiatives that move forward not because the right path was clear but because the people involved couldn’t tolerate the discomfort of the unknown and just accepted the first easy path that presented itself. Google X has this whole thing about the monkey and the pedestal…usually, these are the initiatives that go headlong into building the pedestal and don’t have the wherewithal to teach the monkey.

Easier said than done, right? OK, let me get pithy and share a few thoughts & experiences from inside the maze that connect to working in unknown spaces:

- Be willing to explore. Nearly every room in the maze presents the explorer with a choice, because there’s usually more than one way out. You might feel a temptation to speed run the whole thing - pick a direction and just keep moving forward. In the early stages of development, whatever you gain in early velocity you usually lose in multiples later down the line from a poorly considered decision. Inside the maze, I’d poke my head in to consider each of the different options and see which one looked the most interesting. Sometimes I’d take a few steps in and decide to double back and go a different way. There’s very little lost from these early explorations.

- In practice, this looks like doing some early, low fidelity prototyping of a few different options for what you might build, for different ways you might solve a specific problem. The easiest & most obvious solution is rarely the best one. The thing that looks prohibitively complicated at the beginning often reveals a more feasible version of itself as you start to get into it.

- Update your conceptual model regularly. What you knew at the beginning isn’t what you know a few steps in. The more deliberate you are about exploring & reflecting, the more insight you start to unearth. In the maze, you start to see how one room connects to another, how one path intersects with three more. You still might not see the whole thing, but you can find your way confidently between a few different points.

- In practice, this looks like articulating specific hypotheses, designing ways of testing those hypotheses, taking time to discuss observations & insights. See also: Solid, Jelly Vapor.

- Decide at the right level. The naive myth is that you’re in a binary state: either you know where to go and can charge decisively forward, or you don’t know and you’re just doing some sort of handwavey discovery. But that’s not exactly right. As you update your conceptual model, you know enough to make certain kinds of directions in how you move forward. You can close off certain directions, you can engage in other directions in more specific ways. The risks come from either persisting entirely in a state of indecision or getting too far out over your skis because you made a bigger decision than you were actually ready for. In the maze, the former is how you grow hopeless and the latter is how you get lost.

- In practice, this looks like starting with very small tests of the basic core risks with relatively loose metrics, and over timing growing more expansive and more precise. Early tests are small, quick, and cheap. They are less about getting the answer right and more about maximizing how much you learn in order to eventually get the answer right - which is fine when it’s small, quick, and cheap. It’s easy to retreat and regroup when you haven’t committed much to it yet.

That’s how you survive the maze. Whether that means how to escape from it or how to grow so comfortable in it that it becomes home, I’ll leave that up to you.

Member discussion